What comes to mind when you try to picture a scientist? Maybe a nerdy white man in a lab coat who writes complicated research papers and can’t communicate with ordinary people or deal with emotions?

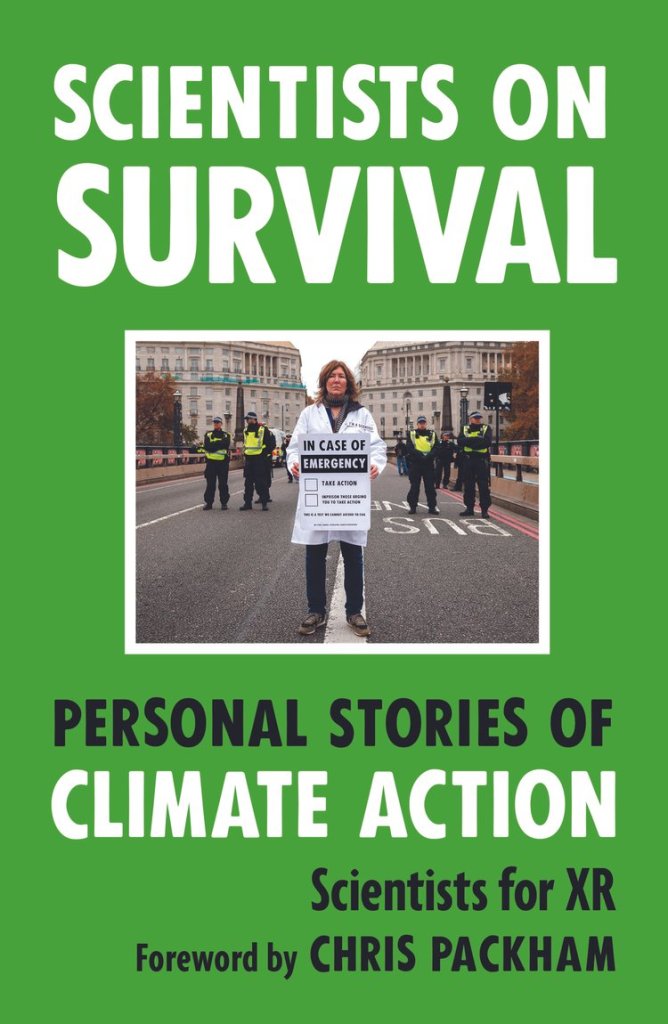

It most certainly won’t be someone so concerned about humankind’s survival that they risk arrest and even get imprisoned for protesting about the lack of Government action on climate change and then write about how they feel and why they did it. So the new book “Scientists on Survival” is quite an eye-opener. Twenty-five scientists, including biochemists, mathematicians, physicists, and ecologists, tell the story of what led them to become activists and weave the science that motivated their actions into powerful human stories.

One such scientist is Aaron Thierry PhD, known to many in Sheffield because he founded the Sheffield group of Extinction Rebellion, calling a meeting in the upper room of the Red Deer pub back in 2019 which was packed to the gunnels. Aaron is an ecologist who researched the rapidly thawing permafrost in the far north of Canada. His studies made him acutely aware of the harm being done to the Earth’s life support systems. With such knowledge comes responsibility and Aaron became a passionate advocate for environmental and social justice. His story in the book details how he overcame his anxiety to take part in civil disobedience by glueing himself to the front of the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy building.

Last week I attended the book launch and met some of the other authors. As a former teacher, I had a lot of empathy with Jen Murphy, who is a science teacher. She read some of her chapter which recalls a Y7 lesson about climate change and the reaction of one of her students. “We’re going to learn today about something very important. It’s about how our use of energy resources is causing climate change. Josh puts his head on the desk. “Head up Josh”, I say. We’re going to listen and then do some activities. “But I can’t, I can’t,” he says. I leave him resting while I get on with the starter to find out what the students already know and think. In a quiet moment, I whisper to him “Are you okay? Do you think you can lift your head up and get started?” He is clearly distressed, his neurotype means that sometimes school is difficult and I don’t know what might have happened in the hours before this lesson. He lets out a wail. “I hate it I hate it and hate it”, he shouts louder now his benchmates are looking over. “I thought it was supposed to be getting better and it’s not. We are always learning about climate change. Nothing ever changes, nothing gets better. What are we going to do?” I have nothing for him. I know that feeling. The anguish, the grief, the helplessness. Josh feels the climate crisis like we should all feel the climate crisis. Raw, honest, terrifying. I’m sorry to say you’re right and I’m worried too but nothing I can say can ever be enough.”

Abi Perrin, a life scientist from York, read the story of her sandwich. “ My arrival at Charing Cross Police Station is complicated by the presence of a sandwich in the pocket of the lab coat I’m wearing. The four police officers involved in the booking-in process cannot agree about the correct fate of the sandwich and, told that the sandwich policies are not consistent between London police stations, the four officers discuss the relative merits of the approaches that would be taken at each of their respective stations past and present. In these circumstances, the custody sergeant interjects to inform them that due to the detainment of more environmental activists than anticipated that day, the station currently has no vegan or vegetarian food, which might be a reason in favour of sparing the sandwich in question from destruction. I’m asked to provide assurances that the sandwich derives from a reputable retailer and that I have not tampered with the sandwich. This issue is not resolved before I’m taken to the cell where I’ll spend the next 24 hours.”

We also heard Sophie Paul, a hydrogeologist, describing the genesis of the Community Energy Project at Caversham Weir on the River Thames. Then Emma Smart, a marine biologist, read about her arrest, imprisonment and snap decision to go on hunger strike.

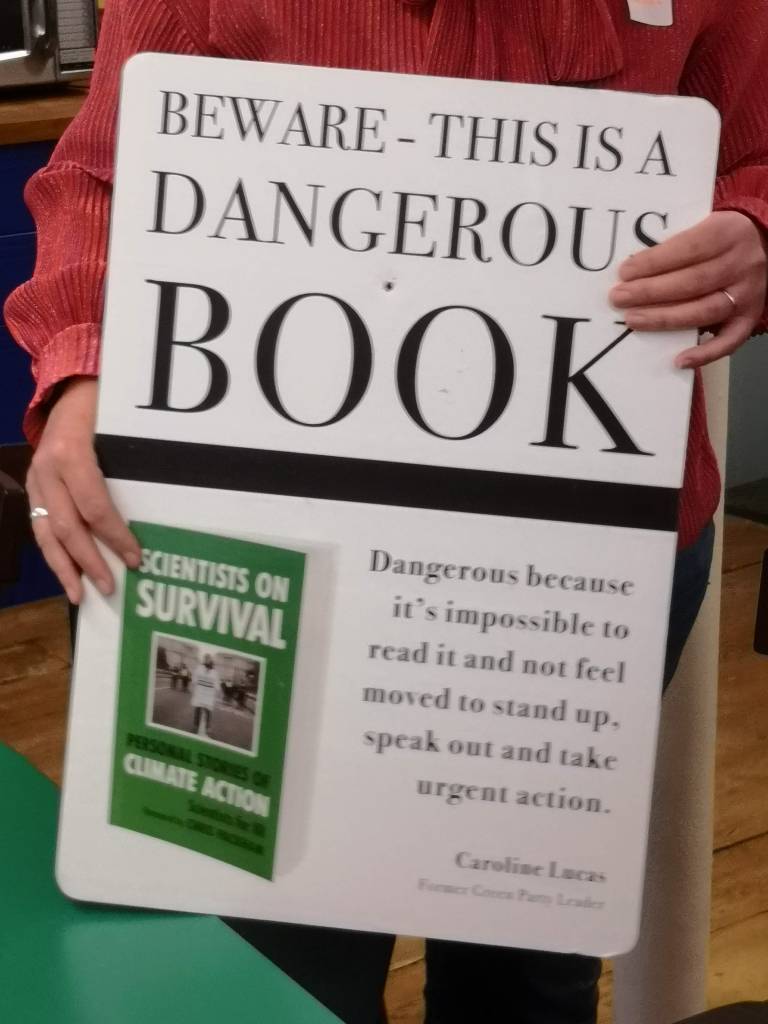

Caroline Lucas noted that this is a dangerous book because it is impossible to read it and not feel moved to stand up, speak out and take urgent action. What has our society come to when politicians and business leaders choose to ignore the warnings of the world’s scientists and continue on the road to extinction? Why are extremely well-educated, peaceful, upright members of our society risking their careers and even going to prison in order to alert us of the extremely dangerous road we are on? And why do politicians like Trump, Farage and Baddenoch get away with talking dangerous nonsense about climate change and still be reported in the media as credible and worthy?

Please read this book and act accordingly.

Transcript from the video.

So this is actually our second book launch but the first public launch for our book, Scientists on Survival. At that first book launch a very talented stand-up comedian and scientist introduced the event saying “Hello I’m Tristram and my natural habitat is Waitrose” and I think my natural habitat is anywhere but standing in front of a microphone. I’d much rather be in a lab learning the secrets of microbial life or out for a walk staring at all the beetles, but I’m here in front of a microphone, a bit uncomfortable but not half as uncomfortable as it takes to get me out on the street in a protest. But we’re living in a strange world. We have an existential climate and nature emergency and that’s what’s pushed myself and 25 scientists who were the authors of this book out to do some things that are quite uncomfortable to us, so each of these 25 stories in this book captures a moment or aspect of a journey of us knowing about the crises that are affecting our world, from that point to then acting as urgently as we can to raise the alarm about them and respond to them. Along the way, each of those scientists in the book, some of whom are here tonight, have had a realisation that may sound kind of obvious to most of you but it was only clear to me after many years of showing a lot of people a lot of graphs that it’s not just facts and data alone that are enough to motivate action. We desperately need action to protect ourselves and the rest of life on Earth but facts won’t get us there, we don’t just need the knowledge we need to feel how important it is we act and we need to see that when we do act we actually do have the power to change things. So each of the authors have found ourselves trying something that doesn’t come naturally to many scientists, speaking from the heart and telling our personal stories as part of this book. Our hope is that in those stories there’s something that motivates, resonates challenges anyone who reads them. So because public speaking kills me I’d like to hand over to three of the authors to share a little bit about themselves and a very short excerpt from the chapter to give you a flavour of what this book’s all about. So starting off with the incredible Jen

Good evening everyone. I’m Jen and I am a science teacher. I live over in Warrington. This afternoon I had year 7. We were doing the components connected in series in parallel if anyone can remember back to their days at school. If they’re not currently a physicist or interested in circuits, but you know dashed over here and it’s really lovely to see so many people here this evening. So this is a short excerpt from my chapter. “Back to the present. I stand in front of my year 7 class. I am nervous. How was I going to deliver the bad news and stay inside the teacher’s standards? How could I handle this? Now that we know what I learned back in the 1980s might happen in the future has actually come to fruition. We’re going to learn today about something very important. It’s about how our use of energy resources is causing climate change. Josh puts his head on the desk. “Head up Josh”, i say. We’re going to listen and then do some activities. “But I can’t, i can’t” he says. I leave him resting while I get on with the starter to find out what the students already know and think. In a quiet moment I whisper to him “are you okay? Do you think you can lift your head up and get started?” He is clearly distressed his neurotype means that sometimes school is difficult and I don’t know what might have happened in hours before this lesson. He lets out a wail. “I hate it I hate it and hate it”. he shouts louder now his benchmates are looking over. “I thought it was supposed to be getting better and it’s not. We are always learning about climate change. Nothing ever changes, nothing gets better. What are we going to do?” I have nothing for him. I know that feeling. The anguish, the grief, the helplessness. Josh feels the climate crisis like we should all feel the climate crisis. Raw, honest, terrifying. I’m sorry I say you’re right and I’m worried too but nothing I can say can ever be enough.”

Up next is Sophie and Jasper (the dog!). Yeah more importantly Jasper’s here so yeah don’t listen to me just watch him. So I’m I’m new to Yorkshire. I’ve recently moved up here and you’ll tell from the story, where I used to live. So this is an excerpt from my chapter. I’m walking over Caversham Weir. The River Thames in spate thundering below flowing onto London and the North Sea. I feel and smell the power- I want to capture that natural energy. Surely someone else wants to too? And they do. A friend of mine directs me to Tony an energetic mind voracious in creating sustainability projects across the town of Reading. It turns out that an application for permission for a hydropower plant has already been submitted to the council through the hard work of local sustainability groups. Together we set up Reading Hydro, formerly as a Community Benefit Society a kind of co-op. We are a diverse collective of warm and tenacious characters. Those are really important characteristics because if you ever have a community group and anybody who has one will know people have got to be warm and kind to each other and also really tenacious otherwise things don’t happen. And we’re scaling the amount of expertise and bureaucracy and administration that’s needed for a hydropower project. Many individuals at some point made a crucial difference to the project. Meant that it could go ahead. There were so many points at which we could have failed and we didn’t because there was one key person among the many of us who made that difference. It was amazing and then there was constant planning networking and vigilance going into attracting the skills we needed. We need so many different skills and the characteristics necessary to make an effective and very responsible organization. It needs to be if you’re doing something that potentially dangerous and above all it was a rewarding organization to be part of. No community organization can survive without this. When we are finally ready to build the pandemic hits. Read for the rest!

So my story follows the immediate aftermath of my arrest for a climate protest and possibly the funniest part of the protest is not part of the story but was an article in the York Mix where they photoshopped me to be the size of Marble Arch and you can look up the article if you’re interested. But it was like you know Godzilla scientists take over London! But this story is about another slightly surreal moment of that protest action. “But my arrival at Charing Cross Police Station is complicated by the presence of a sandwich in the pocket of the lab coat I’m wearing. The four police officers involved in the booking-in process cannot agree about the correct fate of the sandwich and told that the sandwich policies are not consistent between London police stations the four officers discuss the relative merits of the approaches that would be taken at each of their respective stations past and present. In these circumstances, the custody sergeant interjects to inform them that due to the detainment of more environmental activists than anticipated that day, the station currently has no vegan or vegetarian food, which might be a reason in favour of sparing the sandwich in question from destruction. I’m asked to provide assurances that the sandwich derives from a reputable retailer and that I have not tampered with the sandwich. This issue is not resolved before I’m taken to the cell where I’ll spend the next 24 hours.

And finally Emma Smart. Just in case you’re wondering always stick the super glue to your hand so that you can see quite clearly what you’ve done there. I’m Emma I am, I was a fish biologist and I was very happy as a fish biologist actually. I would spend days weeks months out in the field collecting species and measuring them. We love our little gadgets our and writing reports and papers and assuming that the science that I was the information and the data I was gathering would be acted upon by decision-makers and politicians and the people that we vote in power and elect and trust that they will take that science and use it for the greater good. I guess I was wrong. So very disillusioned with academia and science with an increasing climate crisis, nature crisis I made the shift from scientist to activism and something I don’t regret actually because the people I’ve met along that journey have both been incredibly comforting and inspiring and motivating and I’m really pleased that you’ve heard from some of them tonight and that hopefully you’ll read this book because without them I don’t know how I would get through every day. Anyway, this is a short excerpt from my chapter.

I find myself in the back of a prison van. A cramped white plastic cubicle with a small square window to the outside world that is scrolling past. The crowded streets of shoppers a driveby of consumerism and greed, designer shops, a tiny window view of a huge systemic problem. A long queue of people waiting to buy fast food from a burger chain. My heart is heavy but my mind is clear. I made an enraged yet composed decision to stop eating. They could take my freedom but they couldn’t take my commitment to the cause. A hunger strike would be a continuation of my protest demanding action on climate breakdown, a nonviolent escalation to demonstrate how serious I am, and the sacrifices I am prepared to make. After 2 and 1/2 years of nonviolent direct action, I am standing in a prison cell. Bright white courtyard lights burn through the cell window creating sharp shadows of bars on the wall next to my bed. It is 2:00 a.m. and completely silent. I wake several times during that first night each time a stark reminder of where I am like a nightmare you don’t leave on waking. I peer through the window hoping I’d be able to see the sunrise. There are five narrow sections of scratched glass between four thickly painted blue metal bars. As it gets light I become desperate to hear or see birds. A buzzard calls. I can’t see it but I cry for the first time. Thank you very much.

I never saw myself becoming an activist of any kind but the people who I’ve met from doing this work I guess over the last few years have absolutely changed my life and inspire me every single day, so I’m so grateful to these incredible scientists women, humans activists and dogs for making the journey and being with us tonight. So thank you so much. Can I request a round of applause for me!

You can purchase the book from Hive or all good booksellers.

Other Reviews

Discover more from Tell the Truth Sheffield

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Scientists on Survival: Scientists talk from the heart about what the planetary emergency means to them.”